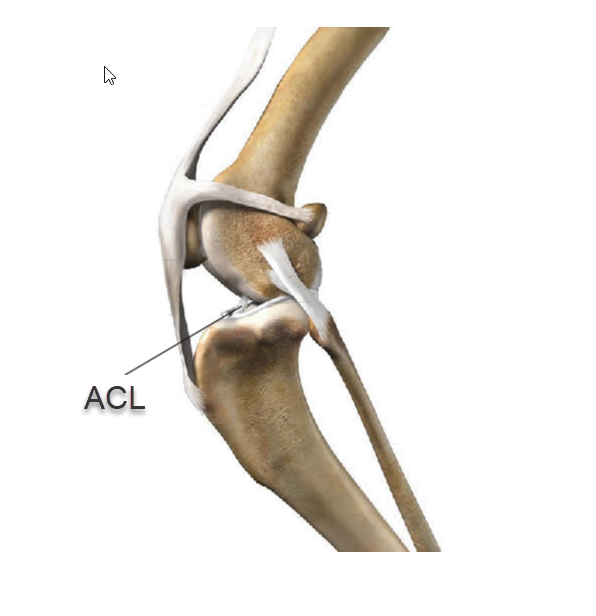

Dogs have the same Anterior Cruciate Ligament (ACL) stabilizing their knee as humans, but it’s commonly referred to as the Cranial Cruciate Ligament or “CCL.” A torn ACL in dogs is one of the most common orthopedic injuries in dogs, and it causes varying degrees of lameness and disability.

Breeds Commonly Affected by ACL Injury

ACL injuries occur in all types of dogs, from the smallest teacup poodle to the 100kg English Mastiff. It is, however, more common in certain breeds (source):

- Newfoundland

- Rottweiler

- Labrador Retriever

- Bulldog

- Boxer

Bilateral ACL injury is common in affected breeds, with 50% of Labrador Retrievers tearing their opposite ACL within one year of the original injury.

How Does A Torn ACL in Dogs Occur?

There is a difference between how people and dogs tear their ACL. In most people, an injury is a traumatic event that occurs during sporting activities (e.g. skiing or soccer). With dogs, the injury is a more chronic condition, where the ACL tears or degenerates over months or years. There may still be a single event where your dog becomes obviously lame, but this usually happens on top of ACL degeneration.

ACL tears in dogs are commonly caused by a combination of factors, including (source):

- Age (frequently 5-8 years old)

- Obesity

- Poor physical condition

- Conformation (steep tibial plateau angle)

- Breed

- Female / neutered

Symptoms of a Torn ACL in Dogs

- Rear limb lameness (limping) of variable degree

- Stiffness

- Sloppy sit or a rapid drop to the floor in the end-stage of the sit

- Difficulty rising from a sit, or down

- Trouble jumping into the car

- Decreased activity level/unwillingness to play

- Decreased muscle mass in the affected leg

- Popping noise (may indicate a meniscal tear)

- Pain (may be displayed as changes in behavior)

Differential Diagnoses

Other causes of rear limb lameness that need to be excluded include:

- Fractures

- Low back pain, IVDD, and sciatica

- Hip pathology (hip dysplasia and arthritis)

- Patella luxation

- Soft tissue strain (e.g. illiopsoas, gracilis)

- Hock / toe injuries

- Bone and soft tissue cancers

Diagnosis

Diagnosis of ACL tears in dogs is typically quite straightforward. Your Vet will use a combination of:

- Observation

- Physical examination

- X-rays

Observation will show varying degrees of rear leg lameness from full non-weight bearing to a subtle change in gait. Your dog may also sit sloppy to the side of the affected knee, so it doesn’t have to bend the knee too much.

A physical examination will demonstrate a decreased range of motion in the knee, with or without palpable swelling. Full flexion (bending) or extension (straightening) of the knee will often elicit a pain response. Any combination of these signs is suggestive of an ACL injury and will be followed up with x-rays for confirmation.

The x-rays will usually be performed under sedation, with the drawer test also being performed at the same time. The drawer test assesses the degree of laxity in the knee joint, as compared to the opposite limb. An ACL tear will have excess movement. The test is performed under sedation as dogs will often tense the surrounding muscles when they’re awake, giving a false negative result.

You may have read on Google or Facebook that x-rays don’t visualize the ACL. That is correct, but they do visualize the tibial slope, any arthritic changes in the joint, and confirm the presence of swelling. These findings help confirm the diagnosis when combined with a good physical examination.

While ACL injury is pretty straightforward to diagnose, rear limb lameness doesn’t automatically indicate ACL tear. The above steps need to be performed well for an accurate diagnosis.

Note: An MRI would be considered the gold standard scan as it visualizes the ACL, but it is usually both cost-prohibitive and difficult to obtain in dogs. If there is any doubt in the diagnosis, and you have the access and the financial means to obtain an MRI of your dog’s knee, then it would absolutely confirm the diagnosis of an ACL tear.

Treatment Options for a Torn ACL in Dogs

Once an ACL tear has been diagnosed, the first major decision you will face is between surgical treatment and non-surgical (conservative) management. The best option for your dog depends on several factors including:

- Age

- Activity levels

- Size

- Conformation

- Degree of knee instability

- Co-morbidities

- Financial constraints

From a theoretical point of view, surgery is considered the gold standard for the treatment of ACL tear in dogs. This is because it stabilizes the knee joint and minimizes arthritis, This, therefore, minimizes pain in the short and long term. However, every case is different and the above factors will be important considerations for your individual dog. Please discuss these with your vet directly.

Surgical Management

If your dog is a good candidate for ACL surgery, your vet will often recommend surgery quickly once an ACL tear has been diagnosed. There are a number of reasons for this recommendation:

- A vast majority of dogs are back to pre-injury activity levels ~6 months post-surgery.

- While knee arthritis is still likely, surgery gives the best opportunity to slow its progress and therefore minimize its impact on your dog’s quality of life.

- The activity restrictions, while strict post-surgery, are much shorter in length.

- Dogs don’t have the same capacity to understand (or cope with) activity restrictions as we do (e.g. it only takes one squirrel after months of good work to undo your dog’s progress). This means that you, and anyone in contact with your dog, need to be committed to overseeing the strict activity restrictions, for an appropriate length of time (often ~12 months), to conservatively manage an ACL tear.

- As owners, it is often easy to think the problem is resolved as your dog improves after their initial acute lameness. However, this is because our dogs are much braver than we are, and only those trained in veterinary rehabilitation will be able to pick up on the subtle long-term lameness. This means your dog is often in pain, without you realizing it.

- There are numerous secondary issues from ACL tears, particularly the risk of concurrent damage to the menisci and other ligaments of the knee. This risk increases the longer there is the instability of the joint, meaning a longer, slower recovery process for your dog.

While performing the surgery as soon as possible is helpful, an ACL tear is not an emergency situation. If you have any hesitancy, take some time to understand your options. If you have any doubt about the diagnosis, seek a second opinion from a specialist vet (orthopedic, sports medicine, rehab).

Surgical Options

There are numerous surgical repair techniques used for ACL injuries in dogs. Different vets will perform different techniques based on their training and the suitability of your dog, so please don’t hesitate to ask your vet questions about the technique they’re recommending.

Some of the surgical options for ACL injury in dogs are:

- Extracapsular (DeAngelis) Repair

- TPLO (Tibial Plateau Leveling Osteotomy)

- TTA (Tibial Tuberosity Advancement)

- CBLO (CORA-leveling Osteotomy)

Surgery does not come without its complications, and while unlikely, if they occur in your dog they can be devastating. You need to take the time to speak to your vet to understand the potential complications of surgery so that you can make an informed decision based on your dog’s presentation.

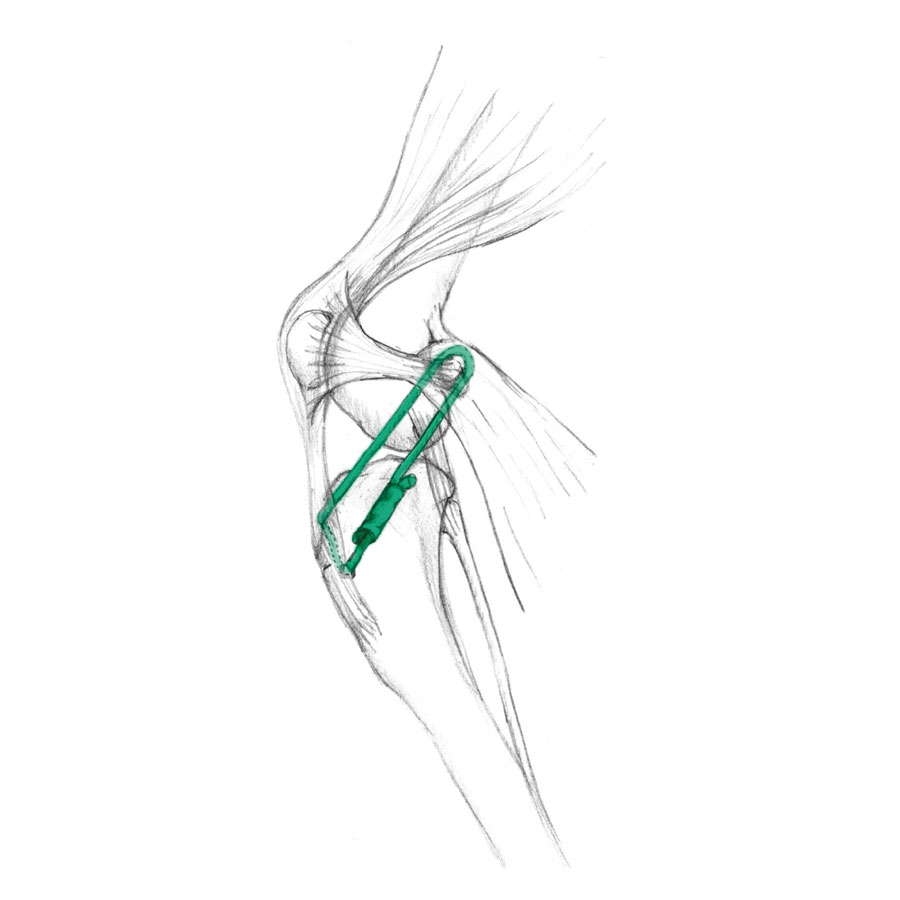

Extracapsular (DeAngelis) Repair

An Extracapsular Repair is a suitable surgical option for ACL repair in smaller dogs (ideally <10kg), or those that live very sedentary lifestyles. It can typically be performed by your general practice vet.

This procedure involves replacing the torn ACL with a thick suture around the lateral (outer) surface of the knee. This suture acts as an artificial ACL for your dog, and therefore works to stabilize the knee joint.

The advantages of this procedure are that it is a much shorter anesthetic, may not require referral to a vet specialist, and is typically cheaper than other surgical options.

The disadvantages however are that this technique relies on significant arthritis forming in the joint to stabilize the knee. It is also not ideal for active or larger dogs (>10 kg) as there is a high risk of the implant breaking. This may mean another surgery down the road to re-stabilize the knee joint.

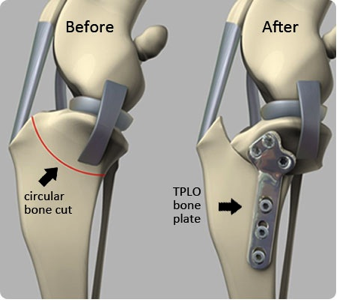

TPLO (Tibial Plateau Leveling Osteotomy)

TPLO surgery is currently considered the gold standard surgical technique for ACL repair and is most commonly used by specialist vet surgeons throughout the world.

TPLO surgery stabilizes your dog’s knee joint by changing the angle of their tibial plateau (the top surface of the shin bone), to make it flatter. The change in tibial plateau angle means that it’s parallel to the ground when your dog is bearing weight. This cancels out the need for an ACL to stabilize the knee.

The TPLO is indicated in medium and large breed dogs that are active. It is the most stable option, minimizing arthritic progression, and allowing for high-impact activities once your dog has fully recovered from surgery. The TPLO is therefore the recommended technique for sporting dogs, young dogs, and those that like to play rough.

The disadvantages of the TPLO are that it is a longer surgery and therefore may not be appropriate for older dogs, or those with co-morbidities. You can discuss this with your vet and may be referred to a specialist to have the surgery performed.

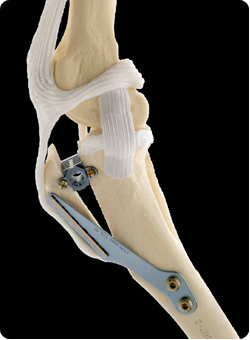

TTA (Tibial Tuberosity Advancement)

The TTA is another osteotomy technique (cutting of the bone) that is used to treat ACL tear in dogs. This procedure involves advancing your dogs tibial tuberosity (the front part of the shin bone) in order to change the biomechanics of their knee joint. This means that the function of the ACL is not required to stabilize the knee.

The TTA is still performed by many vets, however, the outcome may be less than satisfactory, with a higher risk of major complications (source). These risk factors include post-operative meniscal injury, implant failure, bone fractures, and infections. Also, if your dog has a very steep tibial slope the TTA may not be sufficient to resolve the knee instability.

CBLO (CORA Based Levelling Osteotomy)

The CBLO is a newer osteotomy technique (cutting of the bone) used to treat ACL tear in dogs. It is a technique modified from the TPLO procedure and may be more suitable for certain ACL patients. This may be young dogs and those with steep tibial plateau angles. This procedure is however very new and there is minimal scientific data to date.

Some vets may elect to use this technique due to its suitability for some patients in which a TPLO is not the perfect solution. These cases are however rare. It is more commonly used based on the personal preference of the individual vet surgeon.

Conservative Management

Conservative management of ACL injury is an option for dogs that are:

- Poor anesthesia candidates

- Have significant co-morbidities

- Advancing age

- Financial constraints

Conservative management is based on careful activity restriction which provides the conditions necessary for the dog’s body to re-stabilize the knee joint without surgical intervention. The recovery process usually takes ~12 months and needs to be combined with a progressive conditioning program.

It’s important to note that the ACL does not repair. Scar tissue forms within the knee joint to stop the excessive movement. Essentially, the arthritic process is accelerated until it reaches a point where the joint changes provide the knee stability, rather than the ACL.

Treatments such as therapeutic laser, acupuncture, and manual therapy may also be beneficial throughout the recovery. They cannot repair the ACL. They can help with inflammation and assist in making sure your dog is not compensating in ways that put excess strain through their knee joint.

Platelet-rich plasma (PRP) and stem cells are currently being investigated as a potential treatment option that repairs the ACL, however, the research is inconclusive at this stage.

Knee braces may be used as part of the conservative management process. These are usually custom-made to fit your dog’s leg. If your dog tolerates a knee brace it can be an excellent option to provide passive stability to the knee joint. A future article will explore the bracing options.

If conservative management is the best treatment option for your dog ACL tear, the most important factors include:

- Knee bracing: a great option if tolerated by your dog

- Strict activity restrictions: progressive re-introduction to activities at suitable time periods (guided by your vet and/or canine rehabilitation professional)

- Progressive conditioning / strengthening of the limb: Our post-surgical ACL article gives an idea of the type of exercises that may be appropriate through your dogs conservative management journey. Time frames may however differ to the post-surgical recommendations. Your vet or canine rehabilitation professional will be invaluable here.

- Weight management: Maintain / achieve the low side of an ideal weight range for your dog. Yes, your dog may need to go on a diet, especially if their activity levels are being restricted.

- Supplements: Joint supplements can be an important component of the ongoing management to try and manage the arthritic changes.

Conclusion

An ACL tear can seem devastating for you and your dog at the time. Depending on your dog’s individual presentation they may be a good candidate for surgery, or alternatively, conservative management is the best option. Each dog will recover at a different rate, and it’s not uncommon for it to take 6-12 months before your dog has completely recovered.

For this reason, it is important to identify your goals early in the recovery process, so you can aim towards them. Remember to celebrate each milestone as you achieve them. It’s an incredible journey for you and your dog, and you can build an amazing relationship along the way.

For more information on the post-surgical ACL, click here.